William Graham was a 23-year-old Dubliner and member of the anti-Treaty IRA when he was shot dead by the Free State Army in November 1922 at Leeson Street Bridge. There is no plaque or monument to mark the spot of his incident.

William was born in 1900 to William Sr. and Mary Graham, both originally from Wexford. The 1901 census shows that the family were living at 5.3 Cornmarket, the road that links High Street (by St. Audoen’s Church) and Thomas Street. William Sr (43) was a Stationery Engine Driver while his wife Mary (39) looked after their four sons and three daughters. All were Roman Catholic. Myles (15) was a messenger at the GPO and Alice (14) was an apprentice in a shirt factory. John (10), Katie (7), James (5) and Bridget (3) were at school while young William (1) was only a baby.

Ten years later the family had moved around the corner to 4.5 Ross Road, part of the Corporation Buildings. This road connects High Street with Winetavern Street.

The 1911 census tells us William Sr. had died sometime during the last decade. He left his widow Mary (50) along with his children Alice (26), a Cake Packer, John (20), a Van Driver, Cathrine/Katie (17), no occupation listed, and James (15), a Telegraph Messenger. Myles had left the family home by this stage. Bridget (13) and William (11) were both at school. Denis Lennon (54), an illterate single man from Wexford listed as Mary’s brother in law, also lived with the family.

At the time of his death in 1922, William Graham was listed as living at 4 Ross Road which corresponds with the census records. Interestingly, 4 Ross Road is the address given by two insurgents who were arrested after the Easter Rising in 1916. These were Peter Kavanagh, a plumber’s assistant, and Patrick Kavanagh, a fitter’s assistant. The 1911 census shows that there were two Kavanagh families living in the Ross Road Corporation Buildings, however, only one matches the above names.

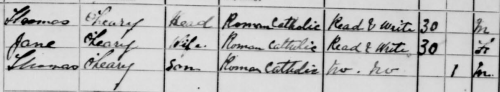

‘Cristíona Ní Fhearghaill bean Seáin Uí Caomhánaigh’ which translates as ‘Christina Farrell, wife of John Kavanagh’ was living at 2.2 Ross Road in 1911 with her three sons and two daughters - Máire (22), Peadar (16), Padraig (13), Samuel (10) and Cáitlín (7). Mary were listed as working as a ‘bean fuaghala’ (seamstress) while Peter is down as a ‘buachaill oiffige’ (office boy). Patrick, Samuel and Kathleen were at school.

Irish Volunteer William Christian from Inchicore recorded in his witness statement that:

On Easter Monday I was mobilised by Peter Kavanagh. He was then living in Ross Road and he desired me to pass on the news to any of the other volunteers who might be perhaps living in the neighborhood. I knew of nobody save my pal, James Daly, so I called fro him and both of us proceeded to Earlsfort Terrace…” (BMH WS 646)

IRA officer Seamus Kavanagh from Clanbrassil Street records in his Witness Statement (No. 1053) that Peader Kavanagh was a member of ‘C’ Company who fought in Bolands Bakery. It is not known where Padraig fought.

It is interesting that the two Kavanagh brothers, living at 2 Ross Road in 1911, would give their address as 4 Ross Road after the Rising in 1916. While I can’t find any evidence that the 16 year old William Graham played any role in the Rising, there is no doubt that he would have been politicalised by the event and, in particular, the arrests of his two neighbors. Or perhaps they were actually living with the Graham family in 1916?

The only reference that I can find of Graham in the Witness Statements from Stephen Keys who was Section Commander of ‘A’ Company, 3rd Batt. Dublin Brigade IRA from 1918-23. Quite bizarrely, he calls him ‘Kruger Graham’ and I haven’t yet been able to find out why. (Kruger seems to be a name associated with South Africa)

Stephen Keys gives a first hand account of the events, that himself and Graham were involved in during the winter of 1922, leading up to his death:

At the next attempt to blow up Oriel House, my job was to take away the men and cover the retreat … I commandeered a car from Leeson St. I was not able to crank the motor and I always had to leave the engines running. The mine went off with such force that you would be blown off your feet … The lads ran by … The last to come was Kruger Graham … (he) jumped into the back of the car and said, “Drive Steve. They are all out. I am the last”

Oriel House, at the intersection of Westland Row and Fenian Street, was the HQ of the feared and hated Free State Intelligence Department. Today, it is owned by TCD and is the headquarters for CTVR, The Telecommunications Research Centre.

Stephen Keys goes on to say that after the aformentioned attempt on Oriel House, their next engagement was “…sticking up an armed guard at Harcourt St. railway.”. He describes this as “a battalion job (with) mostly ‘A’ Company men” involved. We can come to the conclusion that William Greham was a member of the 3rd Batt. of the IRA and quite possibly ‘A’ Company.

Keys writes:

I had another car on this occasion, an open car. They were to bring down the rifles from the railway and load them into the car. Willie Rower was on this job and he shot someone, which disorganised the plan and spoiled the job. I drove around, thinking I would pick up some men who might be straggling around the place.

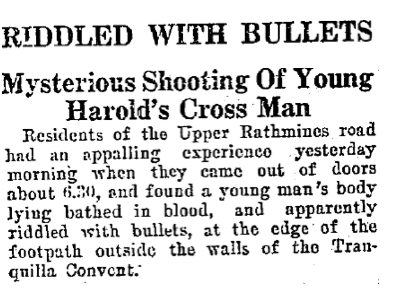

The Irish Independent of 28 November 1922 wrote that a Lt. Comdt. of the Free State Army was “on duty in the vicinity of Harcourt St … with 3 whippet cars and a tender (when) shortly after 9pm … he heard shooting.”. This patrol rushed to Harcourt Station and found one of the guards there had been disarmed.

After finding out what had happened, he collected his men and proceeded along Hatch Street to Leeson Street. Here, three men were spotted by the bridge. The Free State soldiers called on them to halt. Searching the trio, they found nothing on the first man but they discovered that Graham had a fully loaded Webley revolver tucked down his trousers.

This is when the story diverges slightly.

The Free State witness said that Graham made an attempt disarm him which forced him to discharge his weapon. Graham’s comrades maintain that the Free State Lt. Comdt. shot Graham at point blank range once he had found the gun on him. Stephen Keys says:

…Kruger Graham, was captured by the Free State Army in Leeson St. and they shot him dead on the street. They got a gun on him.

As it was punishable by death to be caught with an unlicensed gun, the second scenario is plausible.

After being shot, Graham was taken to a nearby house where a d doctor and two clergy men were called. He was subsequently brought to St. Vincent’s Hospital where he was pronounced dead. Dr. Blanc stated at the inquest that he died due to shock and hemmorhage, caused by a gunshot wound that entered and exited his stomach.

At the inquiry that followed, the unnamed Lt. Comdt. was cross-examined by solicitor John O’Byrne (acting for the authorities) and then Alex Lynn (acting for the next-ok-kin):

Mr. O’Byrne – Have you any doubt that it was your shot that hit him?

Witness – No; he fell when I fired

Mr. O’Byrne – Have you any military instructions as to what to do if a man attempts to disarm you?

Witness – Yes, shoot him

Mr Lynn – Don’t you think it is necessary for a citizen to carry a revolver (in) these times?

Witness – Is it, if he wants to be executed for it

Mr. Lynn – Is it any worse to be executed than to be shot in Leeson Street?

Witness – A man cannon carry a revolver without a permit from the competent military authority.

The newspapers reported that the dead body of “William Graham, aged 23, Labourer of 4 Ross Road” was identified by his brother Maurice. As there are no Maurice Graham’s listed in Dublin in the 1901 census, this is likely to have his brother Myles who was recorded in the Graham family census return.

William Graham was just one of dozens of young anti-Treaty IRA men who were killed by the Free State in Dublin from August 1922 to August 1923. Of the 25+ murders, there are only a handful of plaques.

If you have anymore information about William Graham or his relationship with the Kavanagh brothers, please get in touch by leaving a comment or emailing me at matchgrams(at)gmail.com